I’ll be direct: I need to drive a car because I live in a place where collective solutions either don’t exist or exist only in forms so degraded that using them means accepting a significantly worse quality of life for reasons that are supposed to be virtuous but actually just mean suffering the consequences of state failure while the state itself continues failing. This absolutely isn’t a lifestyle choice or political position. Rather, it’s a material necessity given the actual conditions I inhabit rather than the conditions I wish existed or that urban planning theory assumes should exist. I need to drive because public transit in both cities I’ve lived ranges from inadequate to dysfunctional, because walking substantial distances in sub-tropical heat and humidity means arriving places drenched in sweat, because cycling on streets designed for cars and driven by drivers who don’t expect or accommodate cyclists is genuinely unsafe, and finally because the distances involved in daily life are too long and the infrastructure is too sparse together with alternatives too dysfunctional to manage without a car. And before someone objects that this is exactly the problem, that car dependency creates and perpetuates these conditions, that individual transportation is environmental catastrophe and spatial waste and everything wrong with contemporary urbanism, let me be clear: I know. I’m not defending cars as good. What I’m defending is that they are necessary given the absence of functional alternatives, and that absence is produced by state failure, not by individual choices to drive.

This is not Europe. This needs stating explicitly because much of the discourse around urban transportation, car dependency and sustainable cities imports assumptions and prescriptions from European contexts where state capacity is high, social trust is high, infrastructure investment has been sustained over decades or centuries, and the baseline density patterns were established before automobile dominance and therefore can support transit and walking and cycling in ways that sprawling automobile-era cities simply cannot. When people say “just build metro systems” or “just implement bus rapid transit” or “just create cycling infrastructure,” they’re imagining a state that can plan, execute and maintain complex infrastructure projects without corruption inflating costs or political turnover abandoning half-finished systems. They’re imagining citizens who trust that the state will maintain what it builds, who believe in collective goods enough to pay taxes for them without massive evasion, who have confidence that transit will be safe and reliable because their experience of public services is that they generally work. They’re, too, imagining cities that are already dense enough to make transit economically viable, where mixed-use development puts destinations within reasonable distance, where the built environment was designed for walking before cars existed and therefore has bones that support pedestrian life.

None of these assumptions hold in most places that I’m describing. The state here does not reliably maintain sidewalks, does not prevent police corruption, does not deliver mail consistently, does not provide functioning public services across most domains, and asking this same state to build and operate complex metro systems or BRT networks or comprehensive cycling infrastructure requires belief in state capacity that the state itself has repeatedly demonstrated it doesn’t possess. Social trust is low, reasonably so given history of corruption, abandonment and repeated failures of institutions to deliver what they promise. Citizens evade taxes massively, partly through corruption but also because the return on taxes paid is so poor that paying them feels like throwing money into a void. The cities sprawled during the automobile era, built outward at low density with single-use zoning and car-dependent design, creating spatial patterns that are vastly more expensive and difficult to serve with transit than the dense European cities that grew organically over centuries and then had transit systems added to them.

So when someone says “this city needs better public transit,” they’re correct in the sense that of course it does, everyone would benefit from functional alternatives to driving, but they’re wrong if they think this is actionable advice or meaningful criticism of people who drive. Building transit requires sustained political will over decades, capital investment in amounts that strain government budgets already struggling with basic services, technical competence in planning and execution that’s often absent from procurement and construction processes, resistance to corruption that’s rare in contexts where construction contracts are opportunities for fraud, and requires maintenance culture that keeps systems running after the ribbon-cutting ceremony when political attention has moved elsewhere. The gap between “should have transit” and “can build and maintain transit” is enormous, and pretending it doesn’t exist doesn’t make it disappear.

Let me be concrete about what actually existing public transit looks like in many cities here, because the discourse often treats transit as if it’s a toggle switch where you either have it or you don’t, and having it means having something like Copenhagen or Tokyo (a reasonably functional system). What you actually have is buses.

The buses are operated by private companies under government concession contracts, essentially oligopolies or cartels depending on the city, providing minimum service at maximum profit with little competition and minimal accountability. The buses themselves are often old, poorly maintained, overcrowded during peak hours to the point where you’re pressed against other bodies in ways that would be unacceptable in any other context. The routes are designed for operational efficiency rather than passenger convenience, meaning they funnel everyone through central terminals requiring multiple transfers for trips that would be direct by car, adding time, complexity and points of failure to every journey. The schedules are theoretical at best, with buses arriving whenever they arrive, clustered together in groups of three after long gaps with none, operating according to some logic that passengers can’t discern and that might not exist beyond driver discretion and traffic conditions.

The experience of using these buses is not neutral transportation, it’s exposure to crime, to harassment, in short, conditions that nobody would choose if alternatives existed. Women especially report constant harassment, groping, lewd comments, threatening behavior that drivers and other passengers ignore because it’s so common that intervening would mean intervening constantly. Theft is frequent enough that everyone knows someone who’s been robbed on buses or at terminals, pickpocketing and phone-snatching and sometimes violent robbery, and reporting it is mostly pointless because police response ranges from indifferent to nonexistent. Using transit means accepting these risks as the cost of mobility, that some percentage of trips will involve unpleasant or dangerous encounters, or accepting that you might arrive late or not arrive at all because the bus broke down or the route was suspended/altered without notice.

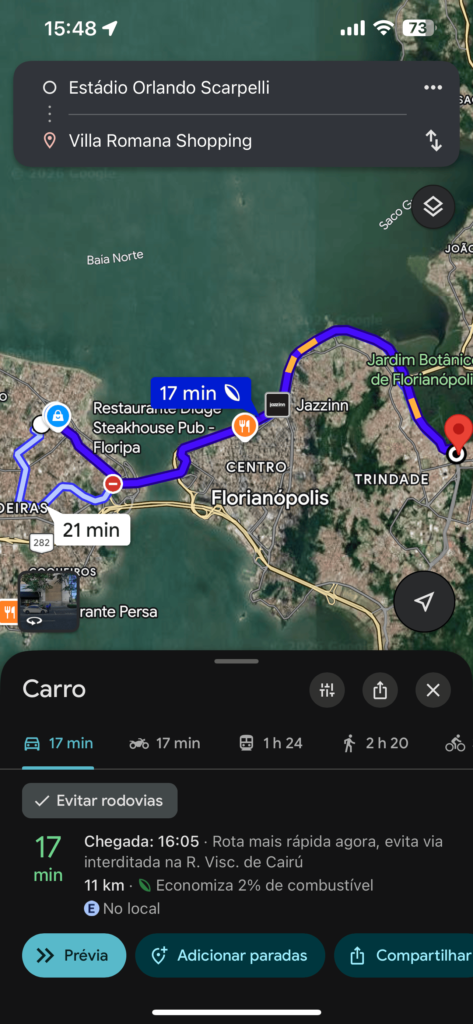

And this takes time. Massive amounts of time. A trip that takes 40 minutes by car might take two hours by bus because of buses that don’t run frequently, transfers between lines, and the traffic that affects buses as much as it affects cars but buses can’t navigate around by changing routes. For people already working long hours, potentially with informal employment, that means no fixed schedule and no guaranteed income if you don’t show up, adding two or three hours of commute time daily is stealing hours from sleep or everything else that makes life tolerable. The time cost is enormous and it falls hardest on the poorest people who have least ability to absorb it.

This is what people mean when they defend driving: they mean they’d rather spend 40 minutes in their own car, in controlled environment with air conditioning, music and the ability to adjust routes if traffic is bad, than spend two hours on buses that are overcrowded and awful. This is simply a rational choice given actual options.

The environmental objection is real and I’m not dismissing it. Cars are environmental catastrophe, contributing to climate change, air pollution, urban heat islands and all the broader ecological disasters that characterize the Anthropocene. Driving a private vehicle for most trips when alternatives should exist is indefensible from pure environmental accounting. But placing this burden on individuals while systemic failures continue is neither fair nor effective as environmental policy.

The reason I drive is because the state has failed to provide functioning alternatives, if reliable safe affordable transit existed, many people would use it, myself included, thus reducing emissions without requiring individual sacrifice or virtue. The absence of transit creates the emissions, not my individual choice to drive within the constraints I actually face. Yes, collectively everyone driving creates and perpetuates car dependency, but you can’t solve collective action problems through individual virtue when the coordination mechanism is absent or dysfunctional.

And let’s be honest about the environmental accounting more broadly. See, Brazilian ‘society’ is organized in ways that are environmentally catastrophic across every dimension: deforestation for agriculture and cattle ranching, industrial processes with minimal environmental regulation, energy generation still heavily dependent on fossil fuels despite hydroelectric potential, consumption patterns that emphasize disposability and waste, construction methods that are resource-intensive and wasteful. Individual transportation is one piece of this but not the largest piece, and focusing on individual driving behavior while systemic environmental destruction continues feels like displacement activity, attacking the visible symbol of environmental damage (the car) while ignoring the structural drivers that are harder to confront because they involve powerful economic interests and political decisions rather than individual consumer choices.

If the concern is genuinely environmental, the solution is building the state capacity to provide alternatives and regulate industrial processes and enforce environmental protection. The solution is not telling individuals “just suffer through dysfunctional transit for the planet” while doing nothing about the broader systemic issues that undersizes individual transportation in their environmental impact.

The geographic and climatic realities matter more than discourse imported from temperate European cities usually acknowledges. Walking 15 minutes in Copenhagen in April is pleasant exercise, easy way to move between nearby destinations, active transportation that feels good. Walking 15 minutes in Latin summer heat, temperature 30-35 degrees Celsius with high humidity (coastal cities), means arriving places visibly sweating, needing to change clothes or at least cool down before you can function professionally or socially. And people surely don’t want to carry the physical evidence of the walk in ways that are socially marked as inappropriate for many contexts. This is not laziness but a fair response to climate that makes pedestrian movement genuinely unpleasant much of the year.

Cycling faces similar climate constraints plus topography. Many cities here are hilly, requiring significant effort to cycle uphill in heat, arriving at least exhausted. The cities that are flat are often sprawling, making distances between origins and destinations too long for cycling to be practical for most trips. And the street environment is hostile: roads designed for cars without bike lanes, infrastructure that’s absent or poorly maintained and many times obstructed by parked cars and utility poles or commercial usurpation. Cycling in these conditions is dangerous. Accident rates for cyclists are high, fatalities occur regularly, and the cyclists are almost always ruled at fault regardless of circumstances because the cultural and legal default is that streets are for cars and cyclists are intrusions.

So walking and cycling, the modes that are presented as obvious alternatives to driving, are in practice much less viable here than in the European cities where they work well. This is, again, the material reality that shapes what transportation modes are actually practical rather than theoretically desirable.

Distance is the other dimension that gets underestimated when importing European solutions. The cities sprawled. This already happened. The spatial patterns are established, with residential areas separated from employment centers, with commercial development in single-use zones requiring car access, with densities too low to support transit economically because there aren’t enough riders per kilometer of route to make service viable at reasonable frequencies. You can’t wish away the spatial structure that exists. You can try to change it through zoning reform and encouraging density and mixed-use development, and these are good policies that should be pursued, but they take decades to produce meaningful change in the built environment because buildings last and neighborhoods don’t redevelop quickly.

In the meantime, people live in the city that exists, not the city that could exist if we started over or if we’d made different decisions 50 years ago. And in the city that exists, the car works because it was designed for this environment. The city is built for cars, and while that’s a failure of planning and a tragedy of urban form, it’s also a reality that can’t be undone through individual choices to use transit that doesn’t adequately serve the built environment.

Retrofitting transit onto sprawl is vastly more difficult and expensive than building transit into density. European cities had density, then added transit. The sequence mattered. Trying to do it in reverse, adding transit to sprawl and hoping density follows, sometimes works but often doesn’t because the land use patterns and property ownership and economic geography are already established in car-dependent forms that resist restructuring. This doesn’t mean it’s impossible, but it means it requires massive sustained intervention over decades, not just building some bus lines and hoping people switch.

Class dimensions are worth addressing directly because they’re real and they complicate any defense of driving. Car dependency hurts poor people who can’t afford cars, trapping them in transit that’s worse and limiting their access to jobs and services and opportunities that car owners can reach. This is genuine injustice, a way that spatial patterns and infrastructure decisions create and maintain inequality. Defending individual transportation can sound like defending privilege or the ability of those who can afford cars to opt out of the dysfunction that the poor must endure.

But the alternative framing is also real: telling middle-class people “just use transit” when transit is dangerous, unreliable and time-consuming, means asking them to accept degraded quality of life for what? Solidarity? Environmental virtue? Those are legitimate values but they don’t override the immediate needs to get to work safely and reliably. And the people usually giving this advice, the ones saying everyone should use transit and car ownership is selfish, are often wealthy enough to have alternatives: they live in neighborhoods where transit is less dangerous, or they can afford private drivers, or they work remotely, or their social position means they don’t face the same safety concerns that others do.

The poor suffer most from car dependency, yes. But they’d also suffer from “just use transit” in contexts where transit barely functions. Until the functioning alternative exists, defending driving is defending the only transportation mode that currently works reliably, and attacking driving without providing alternatives is just attacking people’s ability to function.

The infrastructure deficit is staggering in ways that policy discussions often don’t acknowledge. Even if political will existed, even if funding were available, even if corruption could be controlled, the amount of infrastructure that needs building is overwhelming. Most cities need:

- Complete metro systems built from scratch, not one or two lines but comprehensive networks covering major corridors, requiring tunneling or elevated construction through already-developed areas, requiring decades of construction that disrupts existing transportation and commercial activity, requiring ongoing operations and maintenance that many transit agencies struggle with.

- Bus rapid transit systems with dedicated lanes and signal priority and station infrastructure, requiring taking lanes from cars which is politically contentious, requiring reorganizing entire bus networks which means fighting existing operator concessions and labor arrangements, requiring enforcement so that bus lanes don’t just become regular traffic lanes within weeks of opening. Curitiba did this, but much willpower was required. Long live Jaime Lerner, I guess.

- Cycling infrastructure throughout the city, not just painted bike lanes that cars ignore but physically separated protected lanes that actually feel safe, requiring reconstructing streets to accommodate them, network connectivity so cyclists can reach destinations without mixing with traffic, storage and end-of-trip facilities that mostly don’t exist.

- Sidewalk networks rebuilt throughout, not just repairing what exists but bringing them to accessibility standards with proper width and grade and surfaces and curb cuts and clearing of obstacles, requiring coordination with utility companies whose poles and boxes and lines encroach on pedestrian space, requiring enforcement against commercial encroachment and parking violations.

All of this while maintaining existing infrastructure that’s already decaying, roads with potholes, “slim” asphalt, bridges that need repair, drainage systems that fail during rain, etc. The maintenance alone is enormous, and adding new infrastructure on top of that requires either accepting further decay of what exists or massively increasing infrastructure budgets in contexts where budgets are already strained.

The timeline for building comprehensive transit in a sprawling city is decades, not years. And that’s if everything goes right: if funding continues across political transitions, if construction proceeds without major delays, if corruption doesn’t inflate costs beyond budgets, if technical challenges don’t emerge that require redesigns, if community opposition doesn’t block or delay projects. Almost none of this goes right in practice, which is why transit projects routinely take twice as long and cost twice as much as initial projections.

What are people supposed to do in the meantime? Just not go places? Accept that their mobility is constrained while waiting for infrastructure that might never be completed? The car works now. Transit might work in 20 years if everything goes perfectly, which it won’t. I’m sorry, but real life is really complicated. Reminder: this isn’t an argument against building transit.

In the third world, there’s a deeper issue about social organization and collective capacity that goes beyond infrastructure. You can’t have Scandinavian transit without Scandinavian social trust and state capacity. You can’t import one without the other. The countries where public transit works well are countries where public institutions generally work well, where there’s broad social consensus around collective goods and willingness to pay for them, where state bureaucracies are competent and relatively uncorrupt, where political transitions don’t mean abandoning ongoing projects to start new vanity projects, and ultimately where maintenance culture means things that are built continue functioning rather than slowly decaying until they fail.

I know that this sounds like cultural essentialism or claiming that some societies are inherently incapable of functional institutions, but it’s not. Really. It’s merely observing that institutions are built over time through sustained effort and reform and political struggle, and that institutional quality varies enormously between contexts, and that you can’t just copy infrastructure from high-functioning societies into low-functioning ones and expect it to work the same way. The transit system exists within a broader context of governance and social trust, and if that context is absent, the transit system either won’t get built or won’t function properly after it’s built.

This is why “just build transit” is frustrating as a commandment. It treats transit as technical problem, as if the challenge is just figuring out the right routes and frequencies and vehicle types, when actually the challenge is political and institutional. These are much harder problems that can’t be solved by urban planning. And in the meantime, people need to move around cities, and the car is what works.

I’m not celebrating this. I’m not arguing that car dependency is good or desirable or something to perpetuate. I’m arguing that it’s necessary given the conditions that actually exist rather than the conditions we wish existed. The solution isn’t individuals making different choices, it’s building the collective infrastructure and institutional capacity that would make different choices possible. Until that happens, defending individual transportation isn’t selfishness.

And here’s the contradiction that I can’t escape and won’t pretend to resolve: I know that my driving contributes to the problem. I know that car dependency perpetuates itself, that traffic congestion comes from everyone making the same rational individual choice I’m making, that parking consumes space and resources, that emissions accumulate, that the built environment organizes itself around cars because everyone has cars, creating the spatial patterns that make cars necessary. I know all this, and I don’t need to repeat this any longer. I drive anyway because I have to, since the alternatives don’t work, and because sacrificing my mobility for environmental virtue when systemic issues continue unaddressed achieves nothing except making my life harder.

And this is the trap! Individual solutions to collective problems don’t work, but collective solutions require state capacity that doesn’t exist, and waiting for state capacity to materialize while accepting degraded mobility isn’t viable for most people. So everyone drives, and the city gets worse for everyone.

The way out exists in theory, as I’ve discussed before. But, once again, that’s a multi-decade project requiring political will and institutional competence and sustained investment, and it’s not happening at the pace or scale required, so in the meantime we’re trapped in an equilibrium where everyone knows the current pattern is unsustainable but changing it seems impossible.

I would love to live in a place where I didn’t need a car, where transit was reliable and safe and comfortable, where walking and cycling were pleasant and practical for daily needs, and the built environment was dense enough as well as mixed-use enough that most destinations were close. But I don’t live in that place, at least yet. I live here, requiring a 2 ton metal box to go anywhere, and defending driving is defending the only thing that currently works even though it doesn’t work well and shouldn’t have to be necessary. This is not Europe; pretending otherwise doesn’t change it.

Leave a Reply